12. Multiple Linear Regression

Multiple linear regression is really an extension of simple linear regression when there are multiple predictors \(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_k\).

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align*}

y_i & = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i1} + \beta_2 x_{i2} + \ldots + \beta_k x_{ik} + \epsilon_i, \quad i = 1 , \ldots , n \\

\epsilon_i & \overset{iid}{\sim} N (0,\sigma^2)

\end{align*}

\end{split}\]

The compact representation can be written as follows, using matrix form.

\[\begin{split}

\mathbf{y} =

\begin{bmatrix}

y_1 \\

\vdots \\

y_n

\end{bmatrix}_{n \times 1}

\quad

\mathbf{X} = \begin{bmatrix}

1 & X_{11} & \dots & X_{1k} \\

1 & X_{21} & \dots & X_{2k} \\

\vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\

1 & X_{n1} & \dots & X_{nk}

\end{bmatrix}_{n \times p}

\quad

\boldsymbol{\beta} =

\begin{bmatrix}

\beta_0 \\

\vdots \\

\beta_k

\end{bmatrix}_{p \times 1}

\quad

\boldsymbol{\epsilon} =

\begin{bmatrix}

\epsilon_1 \\

\vdots \\

\epsilon_n

\end{bmatrix}_{n \times 1}

\end{split}\]

\[

\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{X} \boldsymbol{\beta} + \boldsymbol{\epsilon}

\]

There’s an elegant closed-form solution for finding the \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\) estimates in classical statistics:

\[

\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^T \mathbf{y}

\]

The estimates \(\hat{\mathbf{y}}\) can then be found by \(\hat{\mathbf{y}} = \mathbf{X} \hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\).

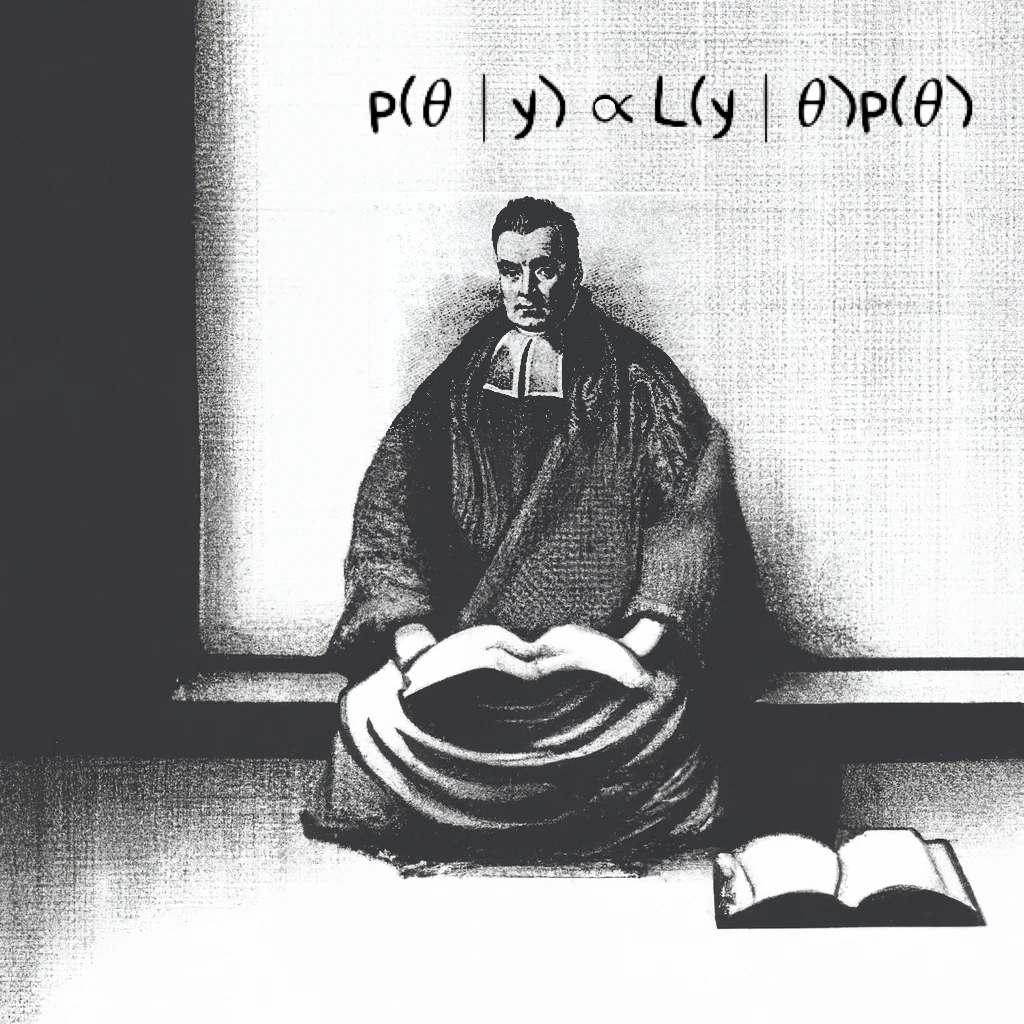

In the Bayesian form of multiple linear regression, we place priors on all \(\beta\)’s and \(\sigma^2\).

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align*}

y_{i} & \sim N(\mu,\sigma^2) && \text{likelihood} \\

\mu & = \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta} && \text{deterministic relationship} \\

\beta_j & \sim N(0,\sigma_j^2) && \text{prior: } \beta_j, \space j = 0 \text{ to } k \\

\tau & \sim Ga(a,b) && \text{prior: } \tau \\

\sigma^2 & = 1/\tau && \text{deterministic relationship}

\end{align*}

\end{split}\]

We typically assume that the \(\beta\)’s are independent. For non-informative priors, we might set \(\sigma_j^2\) to something large, like \(10^3\) or \(10^4\), and the \(a\) and \( b \) parameters in \(\tau\)’s Gamma distribution to something small, like \(10^{-3}\).

An example using independent Normal priors on \(\beta\)’s can be found here: Taste of Cheese.

Other methods for defining priors, such as Zellner’s prior, may help to account for covariance between predictors.

\[\begin{split}

\begin{align*}

\boldsymbol{\beta} & \sim MVN(\mu,g \cdot \sigma^2 \mathbf{V}) && \text{prior: } \boldsymbol{\beta} \\

\sigma^2 & \sim IG(a,b) && \text{prior: } \sigma^2

\end{align*}

\end{split}\]

\[

\text{typical choices: } g = n, \quad g = p^2, \quad g = \max\{n,p^2\}

\]

where \(\sigma^2 \mathbf{V}\) is the covariance matrix. An example using Zellner’s prior can be found here: Brozek Index Prediction.

Authors

Jason Naramore, August 2024.