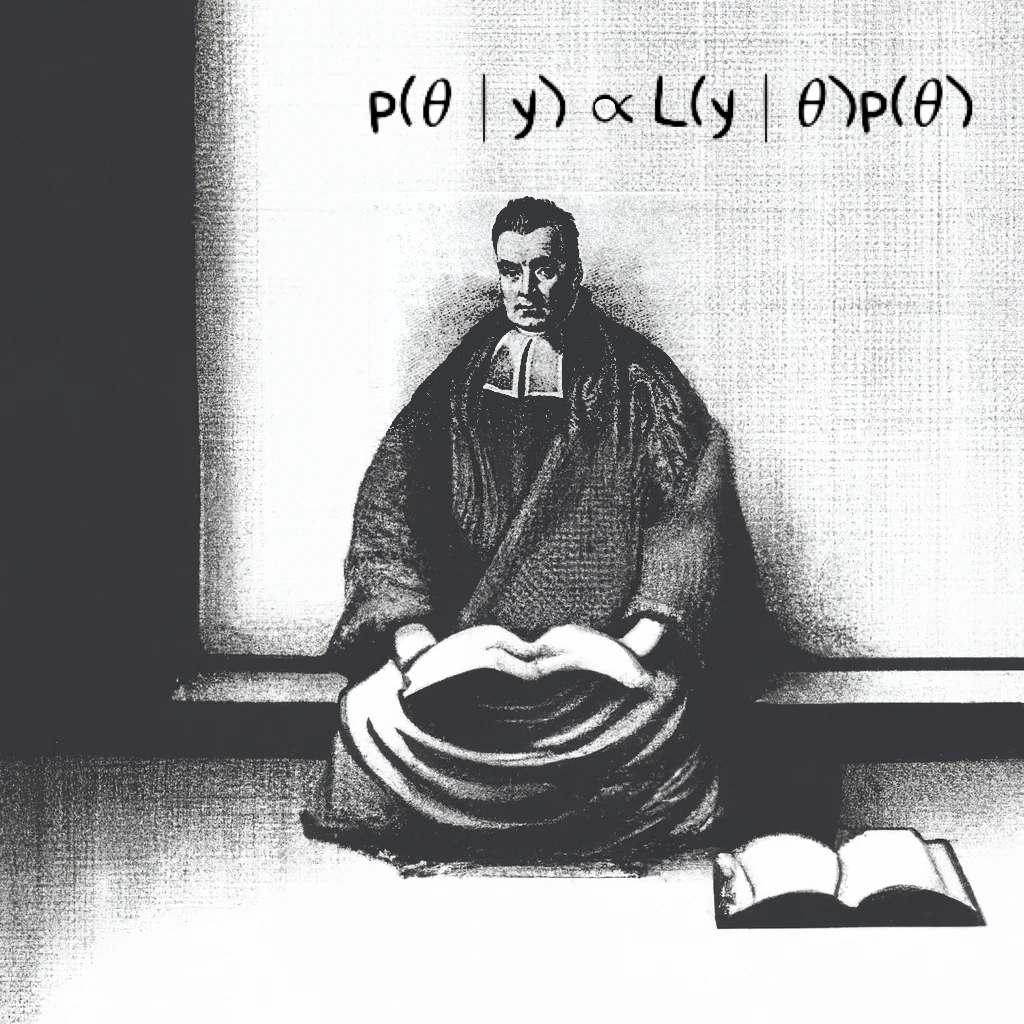

15. Non-informative Priors#

What if we don’t have any prior information at all?

Objectivism and the search for truly non-informative priors#

Priors ideally would be based on prior beliefs or knowledge about the parameter in question. But in reality, we don’t always have a strong belief about something, so we might use non-informative priors. That, and criticism from frequentist statisticians, led to people looking for the “objective” best non-informative priors, for some definition of objective. These are also sometimes called reference priors.

[Kass and Wasserman, 1996] has an excellent overview of the different methods for selecting reference priors through 1996, including Jeffrey’s priors, Zellner’s method, Jaynes’ principle of maximum entropy, Kullback-Leibler divergence, and more.

At the risk of oversimplification, it seems useful to identify two interpretations of reference priors. The first interpretation asserts that reference priors are formal representations of ignorance. The second asserts that there is no objective, unique prior that represents ignorance. Instead, reference priors are chosen by public agreement, much like units of length and weight. In this interpretation, reference priors are akin to a default option in a computer package. We fall back to the default when there is insufficient information to otherwise define the prior…

The first interpretation was at one time the dominant interpretation and much effort was spent trying to justify one prior or another as being noninformative… For the most part, the mood has shifted towards the second interpretation. In the recent literature, it is rare for anyone to make any claim that a particular prior can logically be defended as being truly noninformative. Instead, the focus is on investigating various priors and comparing them to see if they have any advantages in some practical sense.

—Kass and Wasserman [1996]

I don’t want to put words in anyone’s mouth, but based on this class, I would say Professor Vidakovic leans towards the objectivist side of Bayesian analysis. We’ll almost always use non-informative priors in this class. While this isn’t a bad choice for an overview course, I want to make people aware that many influential people in the field today don’t recommend using noninformative priors in practice (see also the prior elicitation section of the previous page.

[Berger, 2006] is a good paper on the debate between objective versus subjective Bayesian analysis (link here). If you only read one paper on this debate, though, I would go with Beyond subjective and objective in statistics. [Gelman and Hennig, 2017], available here.

Improper priors#

We will occasionally encounter improper priors (especially Jeffrey’s priors). An improper prior is a prior distribution whose integral does not integrate to a finite number.

Despite their mathematical irregularity, improper priors can often be used in Bayesian analysis without issue. This is because we seldom integrate priors by themselves; instead, our requirement is that the product of the prior and likelihood function result in a proper posterior distribution.