6. Analysis of Variance#

One-Way ANOVA#

In an ANOVA model, we are trying to discern whether the means of \(G\) different treatment groups are equivalent or different. The null hypothesis is that the mean of all treatment groups are equal:

The ANOVA model is defined as

Here, \(i\) enumerates the treatment groups, \(j\) enumerates the sample points, \(\mu\) is the overall mean (grand mean), and \(a_{i}\) represents the \(i\)-th treatment’s deviation from the grand mean (treatment effect size). Notice the implication of the hierarchical structure introduced earlier in Unit 7.

Since under the null hypothesis, the group means are equal to the grand mean:

Observe we could also write our null hypothesis as:

In classical statistics, an ANOVA table is built and an \(F\)-test is used to determine if \(H_0\) is rejected. Note that the rejection of \(H_{0}\) only implies that presence of a difference was detected. Additional methods are required to identify which group means are significantly different from each other.

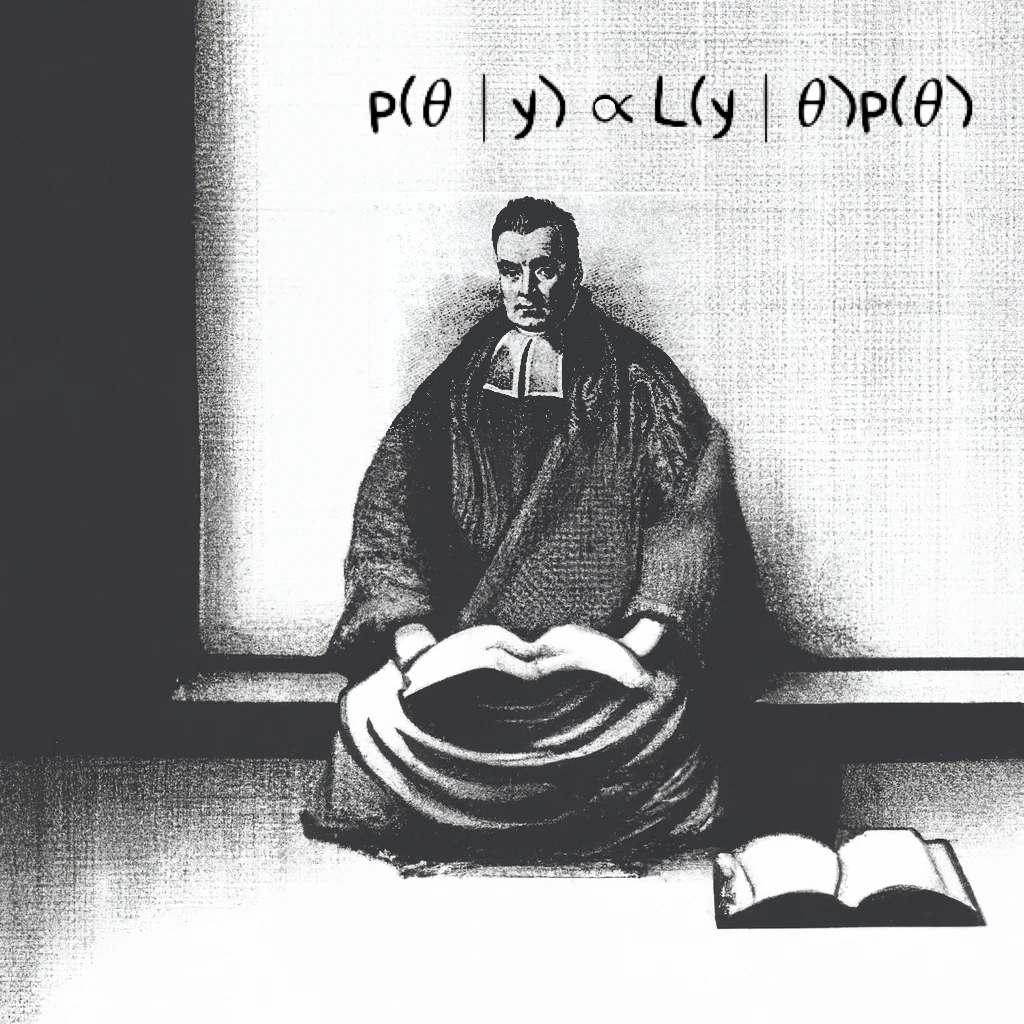

The Bayesian approach to ANOVA is to set priors on \(\mu\), \(a_1,a_2,...,a_G\), and \(\sigma^2\). The Bayesian model is constructed as:

Here \(\sigma_0^2\) and \(\sigma_i^2\) are representing prior variances of the grand mean and treatment groups, respectively. Non-informative variances might be something like \(\sigma_0^2 = 1000\). To assess \(H_0\), we will look at the posterior distributions of the \(a_i\)’s to see if they are significantly different than zero. If we want to compare treatment groups, we can calculate their difference in the Bayesian model, and then look at the posterior distribution of the difference to see if it’s significantly different than zero.

This is another example of how Bayesian modeling allows for direct specification and interpretation of hypotheses in the “same world that the data live in”. Other methods for Bayesian model evaluation exist, and you will be exposed to a few throughout the remainder of the course.

Warning

Suppose instead that we specified only:

The joint log-likelihood would be:

Now consider a shifted parameterization:

The new joint likelihood is:

…the same as the first joint log likelihood. This is problematic. Without constraints on \(\mathbf{a}\), there exist infinitely many combinations of \((\mu' , \mathbf{a}')\) that yield the same likelihood value. When this happens, the model is said to be non-identifiable or unidentifiable. You can learn more about the concept of identifiability in statistics here.

In the frequentist paradigm this results in a non-unique maximum likelihood estimate (MLE). In the Bayesian paradigm, the posterior may, under circumstances, become non-integrable. In both cases, computational methods such as optimization or MCMC sampling may fail to converge, resulting in unreliable parameter estimates.

If, in your assignments or projects you define a Bayesian ANOVA but convergence fails, check to make sure you have specified your model in a way that is identifiable.

Recall that in any mean-centered sample, the signed deviations from the mean sum to zero. In a similar manner, imposing the sum to zero (STZ) constraint on \(\mathbf{a}\) ensures a unique solution and preserves the interpretability of each \(a_{i}\) as a centered deviation from the grand mean. Some examples of how to do this in PyMC are provided in future lessons.

Note

Notice that in the frequentist formulation, there is no \(\sigma_i^2\) , \(\sigma_j^2\), or \(\sigma_{ij}^2\). This is deliberate: frequentist ANOVA assumes homoscedasticity, meaning constant variance across all groups. If this assumption is violated—especially when sample sizes differ—it can lead to increased risk of Type I or Type II errors.

In the Bayesian framework, we may place separate priors on each \(\sigma_i^2\), allowing us to relax the homoscedasticity assumption when appropriate. However, because the choice of priors on variance components can affect both model behavior and interpretation, homoscedasticity is often retained by choice, even though it is not strictly required.