5. Markov Chain Monte Carlo#

This is going to be our algorithm of choice for the rest of the course. This unit will give us the very basics of Metropolis-Hastings and Gibbs sampling. The goal is to get us understanding just enough to reason about what’s happening under the hood when we start using libraries like OpenBUGS or PyMC in Unit 6.

I don’t have a lot to add to the lecture here, but I’ve added some comments to the lecture slides. This is more of a reference—don’t spend a lot of time trying to understand the algorithm itself here, just get a basic understanding of the concepts below and move on to the next lecture, where we’ll go over the algorithm itself.

Lecture slides with notes#

Our algorithm will generate a Markov chain. It’s a sequence of random variables following the Markovian property, where the conditional probability of the next state depends only on the current state, not any of the previous states. After running our algorithm, we’ll have an array of samples from our Markov chain.

Markov chain definition#

A sequence \({X_0, X_1, X_2, \dots, X_{n-1}, X_n, X_{n+1}, \dots}\) forms a Markov Chain if:

The conditional probability \(P\left(X_{n+1} \in A | X_0, X_1, \dots, X_n\right) = P\left(X_{n+1} \in A | X_n\right)\). This property states that given the present, the future is independent of the past.

Given \(X_n\), the future (events defined on \(X_{n+1}, X_{n+2}, \dots\)) is independent of the past (events defined on \(\dots, X_{n-2}, X_{n-1}\)).

The conditional probability \(P\left(X_{n+1} \in A | X_n\right)\) is equivalent to a transition kernel \(Q_{A | X_n}\).

The transition kernel \(Q_{A | X_n} = x\) can be computed as \(\int_A q(x, y) dy\) which represents the probability of transitioning into set A from state x.

\(\Pi\) is an invariant distribution if \(\Pi(A) = \int Q_{A | x} \Pi dx\). This means that integrating the transition kernel distribution with respect to the distribution \(\Pi\) yields the same distribution \(\Pi\), making it invariant.

Further notes#

\(\pi\) is the density for \(\Pi\). It is stationary if it satisfies the detailed balance equation: \(q(x|y) \pi(y) = q(y|x) \pi(x)\). The detailed balance condition states that for any two states \(x\) and \(y\), the probability of transitioning from \(x\) to \(y\) times the stationary distribution at \(x\) equals the probability of transitioning from \(y\) to \(x\) times the stationary distribution at \(y\).

If \(Q^n_{A|x} = P(X_n \in A | X_0 = x)\), then as \(n \rightarrow \infty\), \(Q^n_{A|x} \rightarrow \Pi_A\). In other words, the \(n\)-step transition probabilities converge to the stationary distribution as \(n\) goes to infinity.

\(\Pi\) is called the equilibrium distribution of the Markov chain. The idea is to construct the Markov Chain such that this equilibrium distribution corresponds to the desired posterior distribution.

The initial condition \(X_0 = x\) is “forgotten” as \(n\) becomes large, meaning that the influence of the initial state diminishes over time. When \(n\) is large enough, each \(X_n\) can be considered as a random variable sampled from the posterior distribution.

Brief history of Metropolis and Gibbs algorithms in papers#

If anyone has more important papers to add to these let me know! This list is very incomplete right now.

1953: Metropolis et al. [1953] publishes the original Metropolis paper.

1970: Hastings [1970] generalizes the algorithm to handle asymmetric proposal distributions.

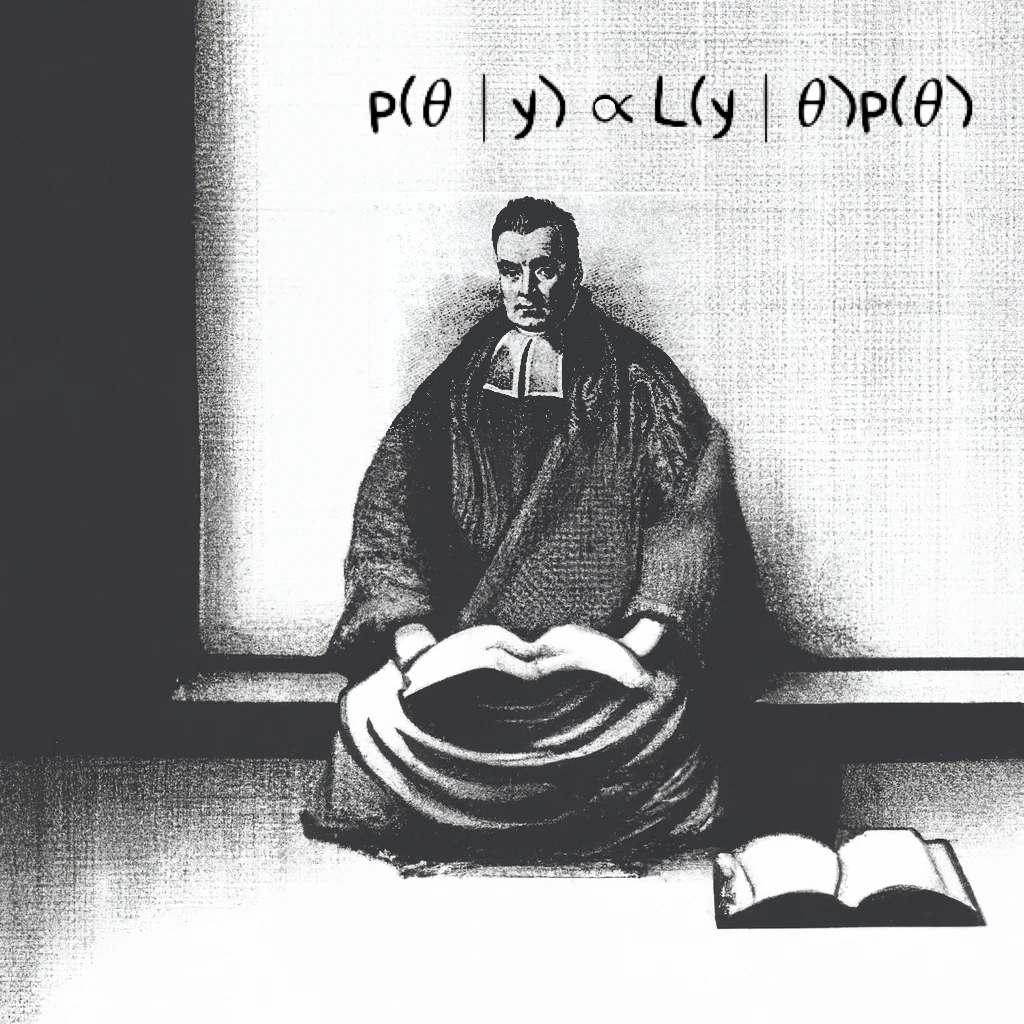

1984: Geman and Geman [1984] use a special case of Metropolis-Hastings for reconstructing images. They name it Gibbs sampling after Josiah Willard Gibbs, a 19th-century physicist whose ideas inspired the algorithm.

1987: Duane et al. [1987] propose Hybrid Monte Carlo, which is now usually called Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC).

2011: Hoffman and Gelman [2011] propose the NUTS sampler, which improves on HMC and eventually becomes the default sampling algorithm in Stan and PyMC.